Who’s heard this yoga instruction?

“Square your hips to the side of the mat in Warrior 2.”

Or even worse: “Square your hips in Warrior 1.”

I absolutely hate this cue.

And not because I’m trying to be contrarian or edgy (although let’s be honest, sometimes that’s fun). I hate it because it fundamentally misunderstands how the pelvis is built, how it functions, and what happens in the body—especially the female body—when we force geometry onto biology.

First off, there is absolutely no part of the body that is truly square in shape. Bones are curved. Joints are asymmetrical. Soft tissue adapts. So why are we using a rigid geometric concept to organize a living, breathing, responsive system?

But the bigger issue is this:

“Squaring” the pelvis often wrenches pelvic joints beyond their functional capacity, creating a cascade of imbalance that shows up as pain, instability, and dysfunction—not just in yoga, but in daily life, pregnancy, birth, and postpartum recovery.

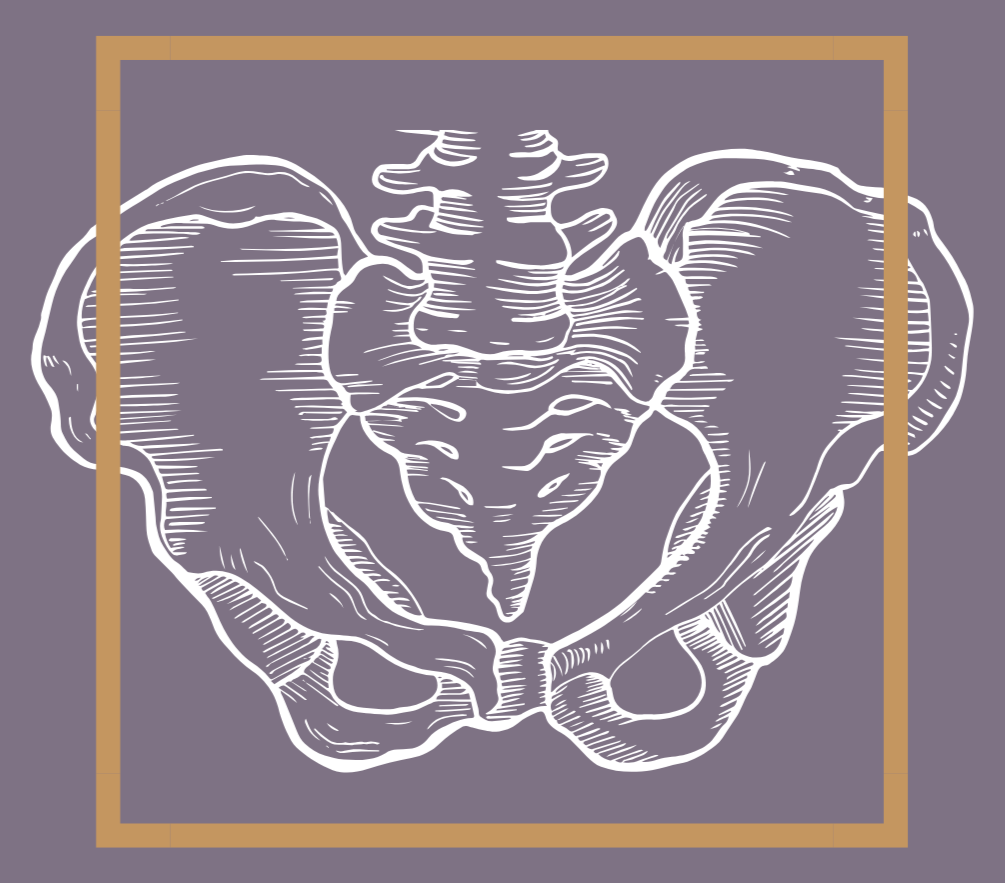

The Pelvis Is Not a Block — It’s a Bowl with Moving Parts

Let’s talk anatomy for a moment.

The pelvis is often taught as a single unit, but structurally it’s a relationship between several bones and joints:

Two innominates (hip bones)

The sacrum

The coccyx

The hip joints (femoroacetabular joints)

The sacroiliac (SI) joints

The pubic symphysis

This is not a rigid ring. It’s a dynamic load-transfer system. Its job is to absorb force, distribute weight, and allow movement between the legs and the spine.

The SI joints are designed for small, subtle motion, not aggressive rotation or compression.

The pubic symphysis is a fibrocartilaginous joint, meant for stability with a touch of give — not repeated shearing forces.

The hip sockets are deep and strong, but their range of rotation varies wildly from body to body.

When we demand full pelvic rotation — especially symmetrical rotation — something has to give.

And the body is very smart. It always takes the path of least resistance.

What Happens When the Hip Can’t Do the Job?

When we rotate the pelvis fully to the side of the mat in Warrior 2, we often drag the femur past what the hip socket can actually perform functionally. If the hip joint hits its limit, the body borrows movement from the next available structures.

Most often, that means:

The SI joint

The pubic symphysis

The lumbar spine

In Warrior 2, fully rotating the pelvis tends to:

Over-open the front side of the pelvis

Strain the front of the pubic joint

Compress the SI joints

Encourage an exaggerated anterior pelvic tilt (“stick your butt out”)

Increase compression in the low back

In Warrior 1, we often see the reverse problem:

The pelvis is dragged forward while the back foot is externally rotated

This creates opposing forces through the pelvic ring

Resulting in shearing at the pubic bone and torsion through the sacrum

These aren’t subtle forces — especially when repeated over years of practice.

Why This Matters Even More in Pregnancy and Postpartum

During pregnancy, hormonal changes — particularly relaxin — increase the pliability of connective tissue. This is essential for birth, but it also means the joints of the pelvis are less protected by passive stability.

Translation:

Most pregnant bodies are about 10% more flexible than they realize.

When we layer poor movement strategies on top of that increased mobility, we often overstretch the very joints that are meant to provide support. This is why so many people experience:

SI joint pain

Pubic symphysis pain

Pelvic girdle pain

Low back discomfort

A feeling of instability or “things not holding together”

And here’s the part that doesn’t get talked about enough:

These patterns don’t magically disappear postpartum.

The nervous system remembers them. The joints adapt. Compensation becomes habit.

The Problem Isn’t the Pose — It’s the Cue

As anyone who has taken the Om Births Teacher Training knows, I’m not a fan of blanket alignment cues. They bypass the specificity required to teach real bodies.

Instead of painting every student with the same brush, we need to look at function over form.

Ask:

What is the intention of this pose?

Where should the movement actually be coming from?

What joints are meant to stay stable?

What joints are meant to move?

What to Do Instead: Let the Pelvis Float

For Warrior 2:

The primary rotation should come from the front hip (the bent knee side). Let the pelvis orient somewhere between the two legs, rather than forcing it to face the side wall.

Yes — this means your hips won’t look “perfectly aligned.”

But your hip socket will stay spacious.

Your sacrum can float inside the pelvic bowl.

Your joints can do their actual jobs.

For Warrior 1:

Allow the pelvis to turn slightly — this is not only acceptable, it’s necessary when the back foot is externally rotated. Let the pelvis lift without tucking past neutral.

Overtucking in lunges creates shear forces in the pelvic joints and increases instability, especially for postpartum and hypermobile bodies.

Instead of locking things into place, look for supported neutrality.

Steady and Sweet

Rather than squaring, let things float.

Find the place where the pose feels both steady and sweet.

Where effort doesn’t turn into gripping.

Where strength doesn’t rely on joint strain.

Ironically, this is where real stability lives.

Try This for Yourself

The next time you’re in Warrior 1 or 2, drop the old alignment rules. Stop trying to make your body match a shape, and start listening for ease, support, and integrity.

Notice:

Where movement feels borrowed

Where effort turns into compression

Where allowing a little more freedom creates strength instead of instability

I’m willing to bet both Warriors will feel more spacious — and more powerful — when you stop pulling your pelvis to the edge of an imaginary square.

If you try this, I’d love to hear what you discover.

Because when we work with the intelligence of the pelvis instead of against it, everything — from yoga to pregnancy to postpartum healing — starts to make a lot more sense.